AMMONITES

Ammonites are common & conspicuous fossils in Mesozoic marine sedimentary rocks. Ammonites are an extinct group of cephalopods - they’re basically squids in coiled shells. The living chambered nautilus also has a squid-in-a-coiled-shell body plan, but ammonites are a different group.

Ammonites get their name from the coiled shell shape being reminiscent of a ram’s horn. The ancient Egyptian god Amun (“Ammon” in Greek) was often depicted with a ram’s head & horns. Pliny’s Natural History, book 37, written in the 70s A.D., refers to these fossils as “Hammonis cornu” (the horn of Ammon), and mentions that people living in northeastern Africa perceived them as sacred. Pliny also indicates that ammonites were often pyritized.

Agricola described ammonites using Pliny's term “Ammonis cornu” in his 1546 book De Natura Fossilium (see title page above).

Conrad Gesner also called these fossils “cornu Ammonis” in his 1565 books De Rerum Fossilium and De Omni Rerum Fossilium (see title pages above).

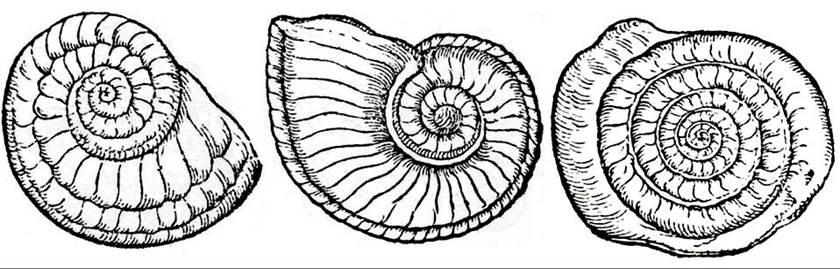

Gesner was the first to include illustrations of ammonite fossils (see below, from Gesner, 1565, ff. 164r & 167v).

Dactylioceras commune (Sowerby, 1815) (5.7 cm at its widest), slightly pyritized, cracked out from a concretion

Stratigraphy & Age & Locality: Whitby Formation, Toarcian Stage, upper Lower Jurassic; Yorkshire coast, England.

William Camden briefly mentions ammonites in his 1607 book Britannia. Ammonites occur in rounded rocks at Huntly Nabb, near Whitby, Yorkshire, England. Camden describes them: “In quibus effractis inueniuntur serpentes saxei suis spiris reuoluti, sed qui plerique capitibus destituti.” (loosely translated from Latin: “Broken specimens have stone serpents inside, coiled up, but generally lacking heads.”)

[click here for an early English translation of the entire Yorkshire section of Camden’s book, by Philemon Holland]

Ammonites from the Whitby area of England have inspired interesting legends & folklore. St. Hilda (614-680 A.D.), an early abbess of Whitby, is said to have cleared the area of snakes by cutting off their heads & throwing them over the cliffs. Whitby locals have been carving snake heads on genuine ammonite fossils for centuries. These “snakestones” have been valued as lucky charms and were perceived to have medical value at one time. Many rocks, fossils, and minerals were long ago considered by superstitious minds to be curatives.

Snakestone (5.0 cm across) - a Dactylioceras commune ammonite with carved snake head, from the Yorkshire coast of England.

Dichotomosphinctes sp. (a.k.a. Perisphinctes (Dichotomosphinctes) sp.) [ID correct?] (5.3 cm across) - commercial specimen attributed to the Oxfordian Stage (lower Upper Jurassic) of Moronodova, western Madagascar.

Cleoniceras madagascariense (5.4 cm across) with preserved shell iridescence. This is a commercial specimen attributed to the Albian Stage (uppermost Lower Cretaceous) of Mahajanga, northwestern Madagascar.

Quenstedtoceras lamberti Sowerby, 1819 from the uppermost Callovian Stage (uppermost Middle Jurassic) at the Dubki Quarry near Saratov, southwestern Russia.

Above left: 3.1 cm across

Above right: 3.8 cm across

Eopachydiscus marcianus (Shumard, 1854) - ammonites could attain large body sizes. Some fossils are so large that they cannot be picked up by one person. Here are a couple Eopachydiscus specimens that are getting to be a bit big. These are from the Duck Creek Formation (upper Albian Stage, mid-Cretaceous) of Spring Creek, Cook County, Texas, USA.

(Bill Van Deventer private collection, displayed at Coral Caverns, off Cavern Street in the small town of Manns Choice, southern Pennsylvania, USA.